The concept of leitmotif – a recurring musical phrase associated with a particular person, idea, or situation – has transcended its origins in opera to become a cornerstone of modern storytelling. From Wagner's Ring Cycle to John Williams' Star Wars scores, this technique of thematic transformation allows creators to weave intricate emotional and narrative tapestries. But what happens when we apply this musical principle to character development, plot structure, and even visual storytelling? The results can be extraordinary.

At its core, leitmotif technique in narrative works operates through repetition with variation. A character's theme might appear in its purest form during their introduction, then undergo harmonic distortion as they face moral dilemmas, eventually emerging triumphant in a major key during their redemption arc. This isn't merely musical decoration – it creates subconscious emotional pathways in the audience's mind. When Luke Skywalker's theme swells as Rey holds his lightsaber in The Force Awakens, generations of viewers feel the weight of legacy without needing exposition.

The power of motivic development lies in its flexibility. A simple three-note motif can represent hope in one context and despair in another, depending on orchestration, tempo, and harmonic context. Similarly, visual leitmotifs might transform across a film's runtime – consider how the color red evolves in Schindler's List, or how the recurring imagery of water in Shape of Water takes on different meanings. This fluidity allows for astonishing narrative economy; a single, well-chosen element can carry tremendous symbolic weight when properly developed.

Modern television has become particularly adept at motivic storytelling. The Game of Thrones score didn't just feature character themes – it allowed them to battle for dominance in the musical landscape as their counterparts did in Westeros. When the Stark theme finally reemerges after seasons of suppression, the emotional payoff is overwhelming precisely because audiences have been conditioned through musical absence. This demonstrates another crucial aspect: sometimes what you withhold matters as much as what you repeat.

The danger, of course, lies in overuse or clumsy implementation. A leitmotif must evolve organically with the narrative, not simply reappear as emotional shorthand. The greatest examples – like the shark theme in Jaws or the descending chromatic motif in Psycho – work because they're inseparable from the storytelling itself. When Marion Crane's car sinks into the swamp, Hermann's music makes us feel the finality in our bones. This is motivic writing at its most powerful.

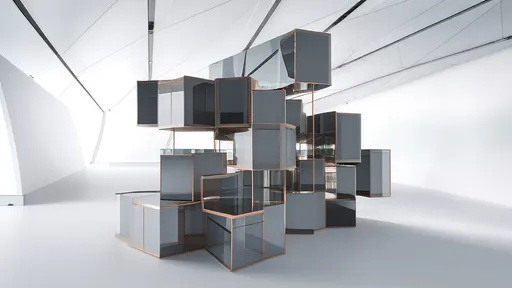

Beyond entertainment, we find leitmotif principles in branding (think of sonic logos like Intel's chime), political rhetoric (repeated phrases that gain power through variation), and even urban design (architectural elements that create civic identity). The human brain seems wired to respond to this interplay of repetition and innovation – perhaps because it mirrors our own psychological patterns of habit and growth.

As storytelling continues to evolve across media, the leitmotif approach offers creators a profound tool for building cohesion in increasingly complex narratives. When executed with subtlety and purpose, these recurring elements don't just support the story – they become part of the audience's emotional memory, creating connections that resonate long after the experience ends. In an age of fragmented attention, that kind of narrative resonance is more valuable than ever.

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025