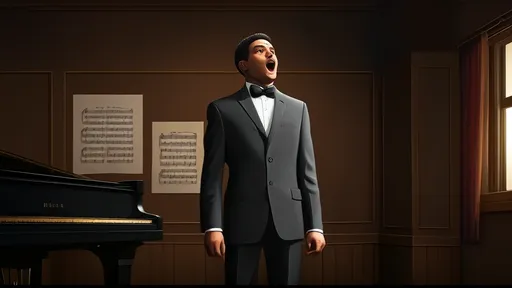

The art of Baroque ornamentation and improvisation in music represents one of the most fascinating yet often misunderstood aspects of early performance practice. During the 17th and 18th centuries, musicians were expected to embellish their parts spontaneously, adding flourishes, trills, and intricate passagework that brought scores to life in ways notation alone could never capture. This tradition was particularly prominent in the performance of slow movements and cadenzas, where the written notes served as mere skeletons awaiting the flesh of the performer’s imagination.

At the heart of Baroque improvisation lay the concept of the "decorated reprise." When a melody returned in a da capo aria or a binary-form dance movement, repeating it verbatim was considered unimaginative—even dull. Instead, performers were trained to vary their delivery with each iteration, weaving new patterns through the harmonic framework. These embellishments weren’t arbitrary; they followed sophisticated conventions grounded in rhetoric and affect. A skilled musician might intensify the emotional tone of a lament by adding sighing appoggiaturas or elevate a joyful theme with sparkling diminutions.

The cadenza—that unaccompanied flourish near the end of a concerto movement—offered the most spectacular arena for improvisation. While modern performers often prepare these passages meticulously, Baroque soloists were expected to invent them on the spot, dazzling audiences with technical prowess and harmonic daring. Surviving manuscripts reveal that composers like Vivaldi and Corelli occasionally notated sample cadenzas, not as prescriptions but as pedagogical models demonstrating the style’s fluid grammar. The true test came when a player had to conjure something equally compelling without preparation, balancing spontaneity with structural coherence.

What makes Baroque ornamentation so distinctive is its inseparable link to dance. The rhythmic vitality of sarabandes, gigues, and courantes permeated even sacred music, encouraging performers to articulate divisions with a sense of physical motion. French clavecinists like Couperin left detailed tables of agréments—tiny graces such as ports de voix and coulés—that functioned like choreographic annotations. Meanwhile, Italian violinists developed the "groppo," a spiraling sequence of rapid notes that mimicked the twisting steps of contemporary ballet. This kinetic quality separates authentic Baroque ornamentation from later Romantic-era virtuosity, which often prioritized sheer volume and velocity over rhythmic nuance.

Contemporary attempts to revive these practices face unique challenges. Modern conservatories emphasize fidelity to printed scores, leaving little room for the risk-taking that defined Baroque performance. Some historically informed musicians now use "controlled improvisation," preparing variations in advance while leaving space for momentary inspiration. Others advocate for a deeper study of partimenti—the bass-line exercises through which 18th-century musicians internalized harmonic patterns and melodic formulas. What remains undisputed is that omitting ornamentation in Baroque repertoire is as radical a departure as adding it would be in a Beethoven symphony.

The legacy of Baroque improvisation extends far beyond early music. Jazz artists frequently compare their chord-scale systems to the rule-based freedom of Baroque diminution. Even in film scoring, composers like Ennio Morricone have channeled the spirit of Monteverdi’s ornamental passaggi when writing vocal lines. Perhaps the greatest lesson from this tradition is that notation was never meant to be a prison—it’s a springboard for creativity, inviting each generation to rediscover the thrill of spontaneous invention within boundaries that paradoxically set the imagination free.

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025

By /Jul 25, 2025